Watch a short video about diagnosis

or scroll down to see the steps

Steps to make a diagnosis

How do you get key information from the patient and the care partner to make a diagnosis? Explore this handout to guide your history.

An approach for taking a history:

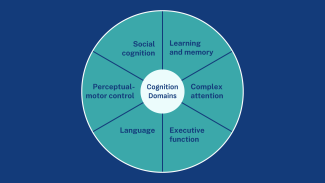

- Ask about cognitive decline. Cognition includes more than just memory, so ask questions about more than one domain.

- How do we know if it's a meaningful decline? Assess the trajectory of decline and the severity of symptoms. A hallmark of dementia is that symptoms are slowly progressive and increasingly severe. For example, your patient is now asking repetitive questions daily as opposed to occasionally.

- Assess function and functional trajectory, i.e. ADLs and IADLs.

- Get collateral. Whenever possible, get a collateral history from someone who knows the patient about their cognitive and functional abilities.

- Be attuned to red flags that signal that a more urgent evaluation is needed. See a list of red flags here.

An approach for doing the exam:

- Do a physical exam to look for certain neurological signs that suggest an etiology: e.g., signs of Parkinsonism, signs of an injury due to stroke.

- Do cognitive testing, if appropriate. Many patients get further testing, such as a longer cognitive test or a full neuropsychological exam, to quantify their cognitive deficits. This can be helpful if available to you and appropriate. For example, you may get more helpful test results in someone with milder or moderate symptoms, but someone with severe symptoms may not be able to participate. Learn more about which cognitive test to consider on our resource page.

How do you use tests and imaging to support a diagnosis? See a summary with more details here.

- Labs: Blood work for reversible causes that are routine to check are thyroid function (TSH), vitamin B12 levels, HIV status, and syphilis. Typically, even if abnormal, these will not fully explain someone's cognitive and functional decline, but they may be contributing factors and should be treated.

- Imaging: Head imaging with head CT or brain MRI is generally recommended to rule out causes such as undiagnosed cerebrovascular accidents and evaluate for signs or patterns of atrophy. A non-contrast brain MRI or CT scan is adequate. Generally, the findings of a brain scan, especially early on in the clinical course of dementia, are of a normal brain scan.

- Emerging diagnostics: Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease are increasingly available via blood tests and PET imaging. They identify the presence of pathology consistent with Alzheimer's disease. This may or may not be available to your patients. These tests do NOT identify other neurodegenerative diseases that can lead to dementia.

Identify and address concurrent conditions and medications that may be affecting cognition.

Comorbidities that can contribute significantly to cognitive symptoms and should be assessed for:

- Sleep apnea and other sleep conditions

- Substance use

- Active serious mental illness, such as a major depressive episode

- Traumatic brain injury or sequelae

If your patient has an intellectual or developmental disability (IDD) that affects cognition, then this should be noted and appropriate adjustments should be made, e.g. cognitive tests should be modified. However, IDD does not mean you cannot assess for a clinical decline consistent with dementia. See this video on adapting your assessment.

Medications that can contribute significantly to cognitive symptoms and should be stopped and/or reduced are:

- Medications with anticholinergic properties. You can use a calculator to assess your patient's anticholinergic burden from medications. Some common examples: diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hydroxyzine, oxybutynin, amitriptyline.

- Sedative-hypnotics. This includes the common medications for sleep and anxiety, such as benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Examples: lorazepam (Ativan), diazepam (Valium), and zolpidem (Ambien).

- Pain medications. Opiates, particularly at higher doses, may affect cognition in the short and long term. Examples: oxycodone, morphine.

- Anti-psychotic medications. These medications are often prescribed for people with severe behavioral symptoms of dementia, but at much lower doses than for people with psychotic symptoms and they carry a black box warning for increased risk of death in people living with dementia. They can also adversely affect cognition. Examples: risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine.

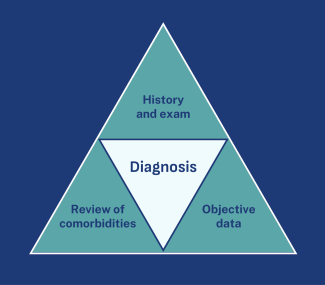

Pull all the information you've gathered together to arrive at a diagnosis. Do you meet the criteria listed in the DSM-5 for dementia?

- Do you have historical and exam evidence that your patient has had a cognitive decline from baseline severe enough to affect day-to-day functioning?

- Do their labs and imaging support the diagnosis?

- Are you addressing comorbidities and contributing medical and psychiatric conditions, or have you identified any condition that may be able to explain all their symptoms?

After a diagnosis, identify what stage your patient is in in the course of their dementia. A person's dementia stage is determined by their functional status, primarily, and it is important to recognize because it gives a sense of care needs and prognosis.

- Mild: some or total functional impairment in IADLs, but minimal impairment in ADLs

- Moderate: impairment in some ADLs (2/more ADL impairments is part of the criteria for skilled nursing home admission)

- Severe: impairment in most or all ADLs (prognosis is typically 1-2 years at this stage)

The CDR scale or FAST scale is often used to stage people and used to determine hospice eligibility (which is typically considered stage 7).

When you have enough information to make the diagnosis, discuss it with patients and their caregivers or care partners. Watch our video on this, and see our resources for more information on how to disclose. Here is an overview of the elements of disclosure:

- Plan to meet with the patient and their care partners.

- Explain what information you have and how this supports a diagnosis.

- Leave time for questions.

- Make a follow-up plan. Too often patients report a "diagnose and adios" experience. They want and need support. Planning a follow-up visit soon to review the condition, their questions, and make further community referrals is a key piece of diagnosis and disclosure.

Create an action plan with your patient and their caregivers or care partners. A separate section of this site reviews the key elements of these plans. And for many clinicians, you will be doing this in partnership with your care team, such as social workers, or community partners, such as dementia-focused organizations. As an overview, the components are:

- Acknowledge and assess the caregiver/s so you can connect them to resources.

- Regularly monitor your patient's cognitive and functional symptoms for progression.

- Help them create an action plan that addresses core issues that arise in dementia, such as advance care planning, safety planning, etc.

Did you know?

Over half of people with dementia are undiagnosed or unaware of their diagnosis.